Filipe Sant’Anna University of Bologna

3rd of March, 2023Everything you need to know about the General Knowledge section, how to engage the questions and how to prepare for them effectively and how to acquire the knowledge as you take a break from your studies.

To score better in the General Knowledge (GK) section of the IMAT, I’d like to share with you guys my own approach to widening my GK without much effort — if you happen to be a nerd like me, at least — and share the content I’ve been consuming over the years that has made me consistently perform well on this part of the test. For reference, I have scored 8 out of 12 (answering 10 and leaving 2 blanks) not only this year, but in my simulation of the 2019 IMAT, and I realized I also knew 8 of the questions asked in this year’s Italian exam. Most people, however, don’t find it as easy, and I hope this will help you find ways of improving your scores over time.

Content Quick Navigation

Introduction

A short while ago I created a post — “IMAT General Knowledge 101 – What to observe when you have no idea what the answer might be”, which is part of this article —, pointing out some overall tips provided by Cambridge Assessment regarding General Knowledge questions. At the time of the post I was very much aware of the fact that the test would be in just a few days’ time, and it was virtually impossible to even try to learn any amount of general knowledge that would be significant for the test. Funnily enough, while discussing the topic of general knowledge I did help a member of the community with the off-hand comment:

“Isn’t it bad enough that they expect us to know Nobel Prizes winners? What’s next, think they’ll expect us to know Fields Medals winners too‽”

Which then introduced her to the Fields Medal just in time to score that sweet 1.5 in this year’s test (2020).

But while the question was made out of incredulity with the seemingly random set of topics appearing on the test, calling them absolutely random or arbitrary would imply giving up on even trying to score better in this section. That would be defeatist, and we wouldn’t be doing our due diligence if we just told you to accept that as reality.

It is true that it is nearly impossible to predict just what will be on the test in any given year, but that doesn’t mean that it is impossible to be better prepared for these sorts of questions. Whereas some topics are always somewhat new, others consistently show up test after test. And while wishing to score all 12 questions might be a bit much, it is not unrealistic to get at least half, if not more of them right in every test.

With results published this week and an entire year ahead of us, those who wish to improve their scores for the next year would do well to start preparing now. With a year’s time it is possible to cover huge amounts of general knowledge in ways that don’t involve memorizing thousands of flashcards for a trivia game night. In fact, learning general knowledge for the IMAT can be a fun and engaging experience, that you can do for leisure, rather than study.

In fact, that’s how I acquired most if not all of my knowledge in this area, just watching some YouTube videos to get my head off the main subjects, or listening to a podcast while driving or doing chores, and reading some books on my free time. I do realize that not everyone is prone to liking all of these activities, but what I’m sharing is my personal sources for content that helped me score high in this section consistently, and hopefully it will be broad enough for people of different learning styles and interests to be able to benefit.

Questions analysis

To optimize our study for General Knowledge, it’s important that we successfully diagnose which kinds of questions are usually present. Afterwards, we need to observe the aspects that comprise the questions and available alternatives, to improve our odds of answering correctly even when our knowledge of the topic is severely limited.

Previous years questions by contents

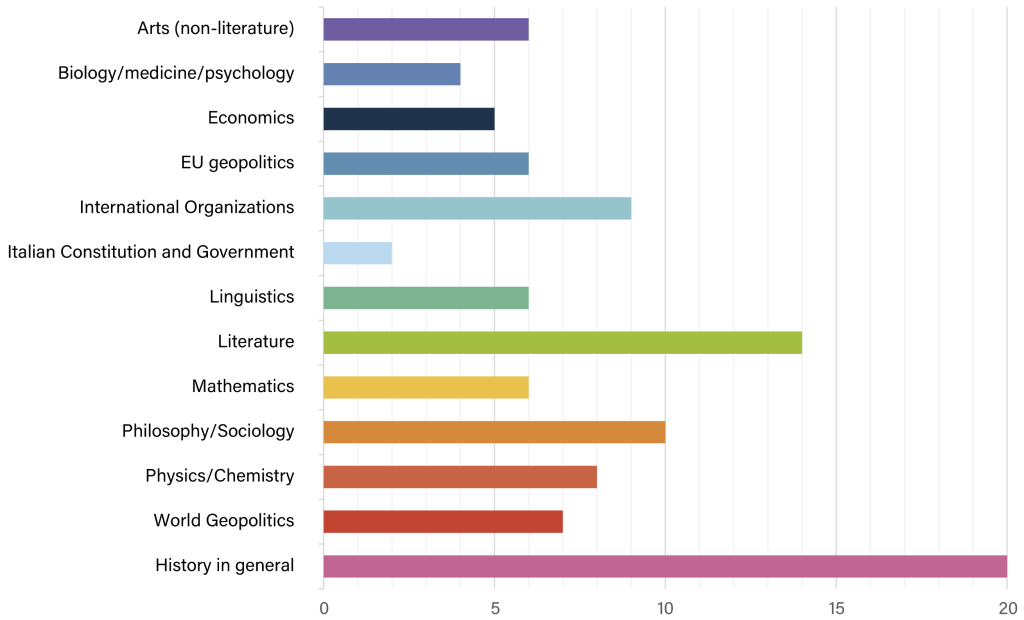

Breaking down all the previous years’ questions (including the Humanitas IMAT’s) we get an outline of the general knowledge expected.

It is well distributed among fields of study (biological sciences, economics, mathematics, philosophy, and physics/chemistry), with extra emphasis on history and literature.

In categorizing the questions, I asked myself:

“Knowledge in which of these fields would help me answer the question?”

So, there’s overlap with multiple fields influencing a single question. While history seems to be the most helpful topic to cover, don’t focus your efforts exclusively on it just yet. That’s because history, of all the categories presented, is actually the vastest, and thus the hardest to exhaust. Instead, it might be wiser to invest effort in getting acquainted with a little bit of each specific field, marking especially notable personalities and their respective contributions.

Knowledge of literature is not restricted to book names and authors, but extends to the history of literature, trends, movements, and styles.

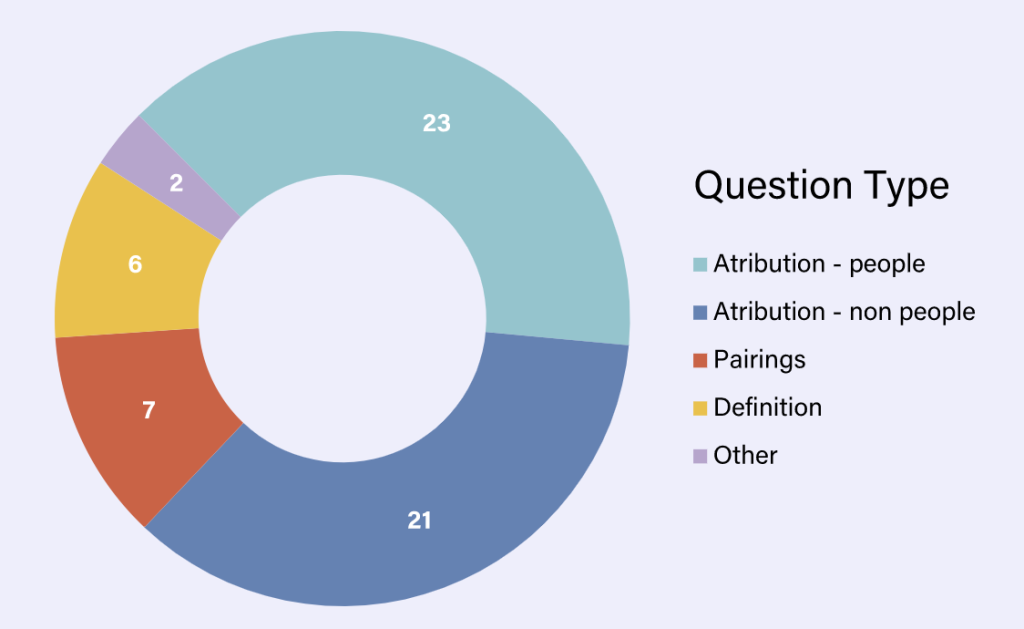

Probably the most marking aspect of the IMAT in this area is that it is very focused on correct attributions — here meaning, who did what, as in “which country signed a treaty in the year 1000?” or “which of these books were written by this author?” — so much so that even questions classified as “pairings” — which of the following pairs of x and y is incorrect — could well be placed in attribution as well.

The division of question types is as follows:

Notice that definition questions are few and far between. Two questions didn’t fit well into any category and were placed in “other”. A total of 59 questions were looked at. This means that general knowledge is very direct in their questions, requiring you to either have previous knowledge of the topic (especially when people are involved) or be able to write off wrong alternatives from the start. In the event that neither is possible, it’s usually a smarter approach to just skip the question entirely.

Moreover, questions can be divided in positive — in which the answer is the only correct option — or negative — in which the answer is the only incorrect option. Generally negative questions are harder than their positive counterparts, because they require either more knowledge on the other areas, or the specific tidbit of knowledge about the wrong option. Still, that doesn’t mean that all negative questions are created the same, nor that they will be the most difficult questions on the test.

For instance, when a question like the newspapers pairings comes up, they often don’t want you to actually know each newspaper of each country. Instead, you were supposed to recognize which of the names corresponded to a newspaper of a different language. We will cover more about this process of getting to the answer further on, but for now, unless the question is covering some very specific topic (such as the setting of the Shakespearean plays) it is safe to assume that the information for the alternatives you don’t know much about is correct. This makes it possible to attain some level of certainty in negative questions, despite their potential for being the hardest.

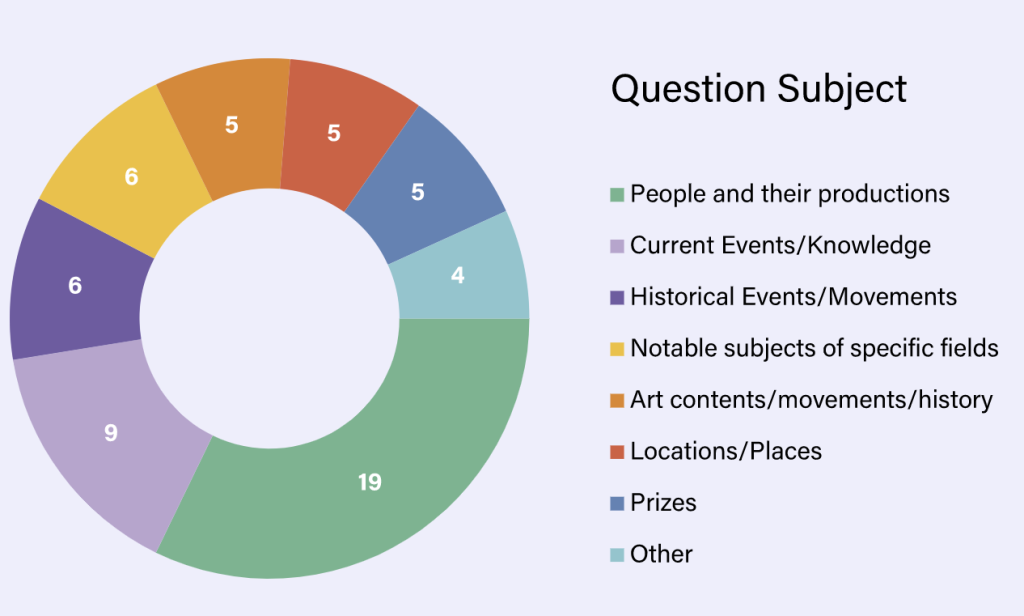

till, the range of fields combined into a single question is the reason why we need to focus on expanding our interests to cover some of the most common GK related areas. Indeed, if we look instead at each of them by subject, the main knowledge required to answer each question is split as follows:

With that in mind, we can start trying to make predictions and give pointers as to which subjects are worth more consideration when studying. Time is of the essence and it is impossible to know every factoid imaginable, but by narrowing down the most recurring topics it becomes possible to focus on those that are more relevant.

Questions: Evolution and Approaches to Topics

The previous section gives us an overall look at how questions are divided, but to understand what is asked we need to take a deeper look at how different questions approach similar topics and wherein their differences lie.

For starters, things like complete biographical knowledge as seen in the 2011 exam’s Dante question clearly turned out unpopular, and the 2012 exam did away with GK altogether.

Which set of statements about Dante Alighieri is correct?

- he was from Florence, wrote poetry, died before 1400

- he was from Milan, was born in the thirteenth century, died before 1400

- he was from Milan, was the son of Giulia Beccaria, wrote poetry

- he was from Tuscany, wrote poetry, was the son of Giulia Beccaria

- he was of noble family, was born in the fourteenth century, wrote tragedies

There was another instance of a seemingly biographic question in the 2015 Humanitas’, with Marie Curie:

Which one of the following statements is NOT true of Marie Curie?

- She conducted pioneering research on radioactivity with her husband Pierre.

- She discovered the chemical elements polonium and radium.

- She was awarded the Nobel prize in Physics in 1903 and in Chemistry in 1911.

- She was the first woman to win a Nobel prize.

- She was the first person to discover X-rays.

So, while these types of question are not entirely out of the question, they’ve become less frequent and their approach substantially changed.

For one, Marie Curie is also a much more relevant historical figure outside of Italy than Dante, with various movies and books based on her life. Her death by the effects of radiation is usually taught in schools — with Pierre’s death of being run over by a horse carriage being almost a joke in the context of the risks of their research — so even though the latter question is technically harder, it ends up being more likely to be answered correctly due to more contact with her life. (In case you’re wondering, she didn’t discover X-rays, and Dante was born in Florence.)

What’s more, the second question actually cares a lot more about notable achievements, accomplishments and contributions, which are exactly the sort of details GK questions tend to be about, they only included lots of information in a single question. Meanwhile the first was very much more biographic, asking that you know approximate year of birth and death, parentage, and place of birth, which are factoids that people are not as likely to remember, as opposed to that Dante was Italian, and wrote the Divine Comedy — one of the most influential works of Italian Literature that has helped shape the language ever since and which features religious motifs such as the emblematic 9 circles of hell (in the first part of the poem, Inferno).

The point of this comparison is to illustrate how the questions evolved in such a short time, and what precisely is expected that you know.

In order to be prepared, then, it is best to focus on figures of significant contribution to the development of the world as most candidates are likely to know it. People with limited geographical influence or of localized significance can be asked about, but they should not be a focus when picking which knowledge to prioritize.

For instance, Mansa Musa, while extremely influential in the History of Mali and possibly being known in countries of Muslim tradition (I’m guessing here, I only became aware of him recently), would place a lot lower on a rank of likelihood to appear on the exam than, say, Jeanne d’Arc — Joan of Arc —, which influenced the story of Europe a lot more. Further, Napoleon would rank way above Joan of Arc, as his exploits influenced Europe already in the colonial age, so had a greater impact in world history (such as forcing the Portuguese Royal Family to flee to Brazil).

Aside from world history, however, a number of questions have featured Italian related knowledge — 16 in total —, excluding the 2 about the government structure. So aside from questions pretraining specifically to features of the Italian government and constitution — which seem like a bias to give Italians an edge against other EU competitors, or against citizens who were not raised in the country’s educational system — questions relating to Italian history (all the way back to Rome), Italian figures (Dante, Primo Levi, Federico Fellini) have constant appearance. So, if you’re in doubt between international content, give priority to those that can be traced back to Italy somehow.

Going into the specifics and the approaches for different knowledge categories, books and authors have featured heavily over the years and literature is the best field to invest time learning about. However, this can be very time consuming and at times the depth of questions can leave the casual knowers hanging. This was seen in the question about the Shakespearian Plays and in the ones about the works of Freud (which showed up in the IMAT and in the Italian exam) and Primo Levi.

Which one of the following plays by William Shakespeare is NOT set in Italy?

- A Midsummer Night’s Dream

- Romeo and Juliet

- Much Ado About Nothing

- Othello

- The Taming of the Shrew

The Interpretation of Dreams and Totem and Taboo are two works by

- Carl Gustav Jung

- Martin Heidegger

- Edmund Husserl

- Sigmund Freud

- Karl Popper

Which of the following books was NOT written by Primo Levi?

- Beyond Good and Evil

- If This Is a Man

- The Truce

- If Not Now, When?

- The Drowned and the Saved

The Italian version was even harder:

Quale fra le seguenti non è un’opera di Sigmund Freud?

- A) Al di là del bene e del male

- B) L’interpretazione dei sogni

- C) Totem e tabù

- D) L’Io e L’es

- E) Introduzione al narcisismo

But, in general, questions like the first are the exception, and trying to be prepared for them would be a fool’s errand. If you already have an interest in classical literature or the details of a specific period in history, by all means explore that knowledge, but simply count yourself lucky if it happens to be on the test. Probabilistically speaking, it’s unlikely.

Still in regards to books and literature, notice that they aren’t exactly narrowed down to world classics, or English classics, or Italian classics, they can be neither or all of them, and their contents can belong to any field (such as psychology or philosophy). Recent tests also have been featuring more of these lists of book names to be associated with their authors, so if you’re checking content about Plato, for example, make sure to create a list of his most influential works:

- The Republic;

- The Symposium;

- Meno; and

- The Trial, which consists of:

- Euthyphro,

- Apology,

- Crito, and

- Phaedo

Do notice, however, that it is less likely that Plato’s works would be the subject of an IMAT negative question, as they have been changed and recompiled over the years, with dialogues being grouped in various ways across different books. I state this based on the observation that previous years have asked much more about authors whose works were published in the past few centuries.

Beyond editorial concerns over contents, another matter that influences this decision is the controversy over the true authorship of some works that have been historically passed as being from one author or another. This uncertainty concerning some of the most prolific authors of antiquity makes them bad candidates for questions, as it could lead to controversy over the very validity of the question or answer.

While, that didn’t prevent them from asking about the Almagest, by Ptolemy, we have way more questions about “recent” works.

Also, the Italian 2020 test features the same book as the Primo Levi question of the 2020 IMAT, i.e. the Nietzsche work, Beyond Good and Evil. Thus, it can be a very good idea to check the Italian exam and go over each question and the answers on the week preceding the exam. If even a single question helps you than that’s already fantastic. This year of 2020 was probably exceptional, with 2 questions being extremely useful, for a total of 3.0 points, but that only serves to illustrate just how useful it can be to go over the Italian questions.

In the past two years we’ve seen at least one question regarding what Italians would learn as “Educazione civica”, which consists mainly of matters of constitutional rights and the structure of the Italian Government, such as who has the power to elect whom, or which governmental body has powers to do something. Here, once again, going over the past Italian exams can offer some light into what might come, as they have been staples on those papers.

In time we will work on the translation of the Italian exams and once they’re ready we can do further analysis of what’s been covered, but for now the sample size is too small to make any meaningful explorations.

One more aspect that needs to be observed is the use of linguistic cues in the construction of alternatives. Knowing more languages (especially romance languages) might not be required, but the fact that nearly everyone taking the test has English as a second language means that they can explore that sort of knowledge. This hardly means questions about vocabulary, like you’d see in the Italian exam, instead they can give you alternatives that feature linguistic disparities with the question.

Which one of the following is the director of the film Amarcord?

- Federico Fellini

- François Truffaut

- Alfred Hitchcock

- Francis Ford Coppola

- Stanley Kubrick

Here, Amarcord can be identified as being an Italian word, which could help one to cross out the last options 3 and 5 at once. François Truffaut is about as French sounding as it gets, so B is also crossed out. This was done with absolutely no knowledge of Cinema or the movie. Don’t be afraid of this sort of thinking. Educated guesses are expected and somewhat encouraged by the IMAT.

Another way to go about it, if you were uncertain whether Amarcord is Italian, as it could also sound French if you don’t know either language enough, would be recognizing that the last three directors are famous American directors. Amarcord, being European limits your options to Fellini and Truffaut.

In fact, another important aspect of the questions is that all the alternatives presented are going to belong to the category requested in the prompt (if somewhat loosely at times). A question about authors will feature names of various authors, books will give you books, Nobel Prize winners for peace will feature personalities known for their influence in promoting peace. Therefore, there’s no need to worry that there will be an answer featuring a painter of similar name or a non-existing person in the alternatives.

This can be good or bad, depending on how you deal with information. The good is that you can be confident that there will be no trick questions designed to confuse you between similar spelling names for the same person, or books that don’t even exist but really sound like they belong amongst the works of that author. The bad is that cognitive biases can lead us astray; reading something that’s familiar can cause us to favour those alternatives when answering, clouding our judgement. So be watchful.

What to expect for upcoming years (speculative)

Having looked at the previous years’ questions, going forward we can expect questions to remain somewhat the same, and follow the examples set in previous years.

If we look at the distribution of questions for the last two years alone (when we’ve had 12 questions), we could expect:

- 1 question of author and literary work

- 1 question of author and work of art that is not literature

- 1 question about some international organization

- 1 question about European geopolitics

- 1 question about a Nobel prize

- 1 question about world history and events

And the other 6 questions can be about any of the previous or some variation, such as:

- geographic knowledge

- some concept or terminology that is specific to some field of study

- the contents of some important work of art

- the accomplishments of some historical figure

- aspects of society relating to some influential philosophy

- economical ideas

Do notice that these predictions can hardly be expected to be 100% accurate, as we’re making assumptions based on the similarities between only two exams (2019 and 2020). However, given all that we’ve learned so far, it would be wise to be prepared for the first group. Aside from the question of “author and work of art that’s not literature” which really stretches the limits of predictability, the others offer some serious narrowing down and allow for much more effective study.

When studying Nobel Prize winners, for instance, it would be a good idea to look into their lives and what they were awarded the prize for.

For European geopolitics, knowing about when each member country joined or when the Euro was adopted is a good idea.

International organizations can be somewhat broad, but make sure that you know what the main acronyms stand for, where their main offices are located and some of their history — because these organizations often came to existence due to important historical events, knowing why they were created, their mission and when this happened can help you in other questions as well — start by those with most international influence and work towards the general of non-EU economic blocks.

World history in general has been more focused on events past the Renaissance. So, while knowledge of Ancient Greece or the Roman Empire is useful in understanding the world of today, it’s been absent from the test thus far. Obviously, the information can help in other questions, but unless you have zero knowledge of any of those events, the basics taught in high school should suffice for most purposes.

Again, I repeat, these are not gospels about what will be on the test, just an analysis of likelihood based on previous questions. To find exceptions you needn’t look too far, there was a question about Hannibal, which was back in the Punic Wars and the one about the Almagest, written at the times of the Roman Empire.

What to focus on if you have no idea

Here the observations of my original post are still valid, so I’ll just adapt it into the article.

Cambridge Assessment published an interesting document , aptly named Preparation Guide, that cover some of the aspects that are usually present in general knowledge questions that should at least help when facing questions for which you are not sure of the answer.

Here’s what the relevant section says:

Section 1: General Knowledge and Logical Reasoning

Section 1 will assess general knowledge and the thinking skills (i.e. logical reasoning) that students must possess in order to succeed in a course of study at the highest level. Such skills are basic to any academic studies, which often require students to solve novel problems, or consider arguments put forward to justify a conclusion, or to promote or defend a particular point of view.

General Knowledge

General Knowledge questions may address a range of cultural topics, including aspects of literary, historical, philosophical, social and political culture.

These questions are not based on any specific part of school curricula; rather their aim is to test the candidates’ interest and knowledge in a wide variety of fields. Candidates with a keen extra-curricular interest in current events and that regularly keep up to date with national and international news will be better prepared to answer this type of questions.

With general knowledge questions candidates may often know the correct answer, however they may sometimes be unsure and may be tempted to give up and move on to other questions.

There are actually some useful strategies that can be adopted to maximise your chances to correctly identify the right answer, as illustrated by the following examples.

EXAMPLE 1:

‘Dubliners’ is a collection of short stories written by which author?

- J. Joyce

- F. O’Brien

- I. Svevo

- F. Kafka

- J-P. Sartre

The correct answer is A. This is a typical literary-based general knowledge question. In the event that the candidate was not already familiar with the literary work in question, it is still possible to try to respond through a process of logical elimination. It is common knowledge that Dublin is in Ireland and therefore it can be safely assumed that the author is Irish. Therefore, the authors with surnames indicating other nationalities can be automatically eliminated, namely answers C, D and E. Now the candidate has narrowed the choice between A and B and has much better chances of answering correctly. Answer B is a “distractor” because it is a typical Irish surname, but one that does not correspond to the author of the work in question. This example illustrates how the student, in case of not knowing immediately the correct answer, can still benefit from a process of elimination using their logical reasoning skills. This approach can lead to correctly responding to a greater number of questions.

EXAMPLE 2:

Which country was governed by the Taliban’s theocratic regime from 1996 to 2001?

- Afghanistan

- Iran

- Iraq

- Saudi Arabia

- Syria

The correct answer is A. This is a typical current affairs/recent history based general knowledge question. This type of question aims to ascertain whether or not students follow recent events and are well-informed on major national and international affairs in the contemporary world. Those candidates who do not actively follow international news and are not keen readers of good quality newspapers and magazines will clearly be at a disadvantage.

EXAMPLE 3:

Which of the following city-monument pair is wrong?

- Stockholm – Pont du Gard

- Rome – Theatre of Marcellus

- Athens – Erechtheion

- Istanbul – Hagia Sophia

- Split – Diocletian’s Palace

The correct answer is A. This is an interdisciplinary general knowledge question based on geographical as well as historical knowledge.

This example can also be solved by using logical reasoning skills – and linguistic skills and intuition, in this case – if the candidate does not know the correct answer immediately.

A possible logical method to arrive at the solution is to first identify the correct matches by recognising the linguistic characteristics of the monuments’ names, even if the candidate does not know those specific monuments in particular. Therefore, answers B, C and D can be safely eliminated at the start. Answer E can be misleading and very attractive because the candidate might not know where Split is (i.e. Croatia) or because he/she might not know that this geographical area was heavily settled by Romans, hence the name “Diocletian”. However, the correct resolution of the question hinges on the recognition that “Pont du Gard” is a typical French name and, therefore, it is not an extremely likely name for a monument in Stockholm, capital of Sweden.

The application of logic skills and linguistic abilities is often successful in solving interdisciplinary general knowledge questions.

EXAMPLE 4:

The World Heritage Convention, adopted by UNESCO in 1972, aims to identify and maintain a list of sites that may be considered:

- of exceptional cultural or natural importance

- of outstanding economic value

- to be characterized by a lasting peace

- to be conventionally suitable for human settlement

- to have exploitable energy resources

The correct answer is A. This is an example of a question based on culture and politics. In this case, the question is about the nature of a world organisation.

Even if the candidate does not have direct knowledge of this topic, the candidate should be able to immediately disassociate the term “heritage” with any answer relating to economy and finance, thus eliminating immediately answers B and E. By the same logic of elimination, C can be de discarded because peace does not relate to “heritage” in any way, leaving only two plausible options and increasing the chances of answering correctly.

Overall, general knowledge questions can cover topics ranging from authors and books to famous personalities, current affairs, history or inventions, world geography and much more. The aim is to test the students’ knowledge of the wider world and their ability to apply logical reasoning in different contexts. The best way to prepare for such questions is to read widely, across a range of different subjects and maintain an awareness of current affairs.

So, as you can see, there are indeed some questions that require us to simply know things, such as current events. But others can be solved or at least narrowed down by logic alone. A key point I’d like to stress is this part here:

Answer B is a “distractor” because it is a typical Irish surname

Observe than that it is done on purpose and that you should be aware of this tactic. If you’re unsure in some question and something is really trying to catch your attention to its similarity to the question topic, take a moment to consider that it might really just be there to bait you into marking the wrong option.

Though I can’t say that I’ve seen this in many past papers, we do have some examples from the 2019 test:

Which one of the following composed the opera Madama Butterfly?

- Giacomo Puccini

- Richard Wagner

- Georges Bizet

- Gioachino Rossini

- Giuseppe Verdi

Rossini was present to try to confuse you with Puccini, due to the similar sounding name.

Which one of the following countries did NOT adopt the coins and banknotes of the Euro as its currency on 1 January 2002?

- Finland

- Austria

- Portugal

- Luxembourg

- Sweden

Here Finland was trying to distract candidates, if they could only remember that adoption isn’t as widespread across Northern or Eastern European countries.

Which one of these events in world history happened most recently?

- The building of the Taj Mahal

- The crowning of Charlemagne

- The October Revolution in the Russian Empire

- The Taiping Rebellion in China

- The fall of the Western Roman Empire

Here the Taiping Rebellion intended to confuse candidates with limited history of eastern events. They could remember the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and mistake them with the rebellion from the 1850’s.

Which one of the following literary works does NOT originate in the corresponding country?

- The Divine Comedy – Italy

- Oedipus Rex – Greece

- The Poems of Rumi – China

- Don Quixote – Spain

- The Tale of Genji – Japan

Again, most of these pieces are very well known, except for the Asian ones (this seems to be a recurring theme), but Genji here is the distractor, but Rumi isn’t a Chinese name, so some knowledge of the cultures and languages would come to the rescue.

That is not to say that every time there will be a distractor, nor that they are always the most attention grabbing like the original Cambridge James Joyce example, but it might be useful to be aware that it is a possibility.

At the end of the day it doesn’t change the fact that this section cannot be objectively studied for, but attention, careful deliberation and sometimes knowing when not to take a bait or skip might earn you or at least save you a few points.

I suggest that you at the very least read the General Knowledge questions at the beginning of the test, even if you don’t know the answers. It may be enough for your brain to refresh some forgotten knowledge you’ve come across along the years. Just give them a glance, see what they talk about, answer any that you’re more certain and come back to them once you’ve finished you test. It may be that nothing changes about your memory, but it can also happen that something sparks back there, and you are able to score some precious 1.5, or 3 points.

The other remarks and examples surely can be applied to more questions throughout the years, and it is worth bringing them to mind when facing a particularly alien question that may be providing you with some clues in regards of where to shoot to. If it can help you narrow things down from 5 to 3 or 2, it may be enough for you to consider a guess.

But in general, don’t count on points from the General Knowledge for your passing grade. If you’re truly relying on those questions to pass, you’re only giving yourself a looser knot to hang, as even with these pointers, the questions revolve around luck of knowing some trivial fact over anything else, and you shouldn’t be feeling bad if you don’t know every piece of curiosity there is about the world.

Resources

Audio-visual resources are great fonts for learning. Also, with YouTube, podcasts and audiobooks you can have control over your playback speed, which can allow you to go through content much faster than the conventional 1x speed. I don’t recommend going straight for a 2.5x as you would probably barely understand, but you can build up to that point.

Start with 1.5x, once you’re comfortable, do 0.1 or 0.2 incremental steps. Always make sure that the new speed is still comprehensible and that you’re in fact retaining the information, before trying a harder level. Over the course of 2 to 6 months you should be able to listen to content at least in 2.0x speed, which can be faster than simply reading.

YouTube

YouTube can be your salvation or damnation and knowing to focus on the good is essential to getting the most out of it. The channels listed below are ones I personally believe in and that I believe that the content produced is thoroughly researched and accurate. It doesn’t mean they have no flaws or that they are always right and unbiased, but they are honest about their content and do work post the highest quality content.

This channel tries to analyze the science behind some iconic POP culture contents (such as cartoons, movies, books or comics). It’s been a while since they’ve uploaded new content, but the content they have put out so far is of good quality without missing out on the entertainment factor (if you like this sort of thing, that is).

This channel goes through a range of topics and curiosities, from distance of planetary orbits to history to well, pretty much anything. It focuses on examining some of the ways we ask questions with their videos and can help us think better in general.

Here we have some good classes in nearly any topic. Literature, Chemistry, Biology, History, you name it, they probably have videos covering those topics. They are more class like than most of the other channels I’m listing here, but the presence of the visuals of videos can really appeal to people and help visualize and internalize lots of contents we go through for the IMAT, so it can also work well for revisions or previews of contents you’ll dive in deeper during your studies. Also, most episodes feature a biography of a historical figure relevant to that topic, which absolutely helps in GK.

Kurzgesagt is just awesome. If you don’t know them yet, you really should. The videos are amazingly animated, their research is pristine and linked in the descriptions (and they’re honest about their earlier videos faults) and they are great for science contents. Their videos feature a bit of biology, astrophysics, and some philosophical questions.

Chemistry only channel. Watch high quality footage and explanations of chemical reactions, really helps you get a sense of separation methods, and if you’re specially attentive, you may really memorize some key reactions or compounds.

This channel is dedicated to explaining how some tech works, it has some really interesting videos, and while not all might be relevant to the curriculum, they can help some concepts get contextualized in day to day appliances (such as the AC video and gas expansion, or the one about different wavelengths of light).

Another great resource for multiple purposes. Features short videos on a very wide range of topics, including literature, math, biology, all under 10 minutes.

Biology turned into a game. While the core of the channel might not be the most useful, since evolution isn’t a key feature of the exam, but again, it features other information in context, which always help us remember those bits later.

Covers lots of diverse topics, from places to technology. Maybe not the most on topic channel on this list, but I find that learning different stuff somehow makes other stuff make more sense, even when they’re not entirely related.

Probably one of the greatest channels to make this list, very comprehensive. Features science of all kinds. I cannot recommend this enough, as it gives you those bits of biographies that go along with some math and physics, which can really help in the test!

Podcasts

Podcasts are a great way of acquiring knowledge. If you chose the appropriate platform (I suggest using the Overcast App if you’re an Apple user) you’ll get no suggestions and your library will only consist of content that you cherrypicked to help you.

Overcast also has the benefit of being able to speed up through non-voice gaps (such as music or just silence that isn’t edited out), which can significantly reduce the length of an episode without even listening to it at a greater speed.

Here are some of the ones I listen to that are relevant for GK, and I’ll not write reviews for them, as they are too many. I’ll mark in bold the ones I already listen to. The ones I’ve picked up but haven’t got around to listening yet will be unmarked.

- 15-Minute History

- 99% Invisible

- A Taste of the Past

- Aaron Mahnke’s Cabinet of Curiosities

- AGE OF VICTORIA PODCAST

- American Journal of Psychiatry Audio

- Benjamen Walker’s Theory of Everything

- Brain Matters

- Byzantium And The Crusades

- Common Sense with Dan Carlin

- Dan Carlin’s Hardcore History

- Drawn: The Story of Animation

- Hidden Brain

- History of Indian and Africana Philosophy

- History of Japan

- History of Philosophy Without Any Gaps

- History Of The Great War

- History on Fire

- In Our Time: Philosophy

- In Our Time: Science

- Invisibilia

- Long Now: Seminars About Long-term Thinking

- Lore

- Making Sense with Sam Harris

- Nature Podcast

- Neurology® Podcast

- No Such Thing As A Fish

- Noble Blood

- ODYSSEY: THE PODCAST

- Ologies with Alie Ward

- Our Fake History

- Philosophize This!

- Psychiatry

- Psychopharmacology and Psychiatry Updates

- Radiolab

- Revolutions

- Robohub Podcast

- Science & Futurism with Isaac Arthur

- Science in Action

- Science Magazine Podcast

- Serial

- Stuff You Should Know

- TED Talks Science and Medicine

- The After On Podcast

- The Age of Napoleon Podcast

- The China History Podcast

- The Fall of Rome Podcast

- The Future Grind Podcast: Science | Technology | Business | Futurism

- The Georgian Impact Podcast | AI, ML & More

- The Great Books

- The History of Ancient Greece

- The History of China

- The History of WWII Podcast – by Ray Harris Jr

- The Learning Scientists Podcast

- The Maritime History Podcast

- The Philosophy Guy

- The Renaissance Times

- The Science Hour

- Tides of History

- TROJAN WAR: THE PODCAST

- Unobscured

- Why Is That Podcast

- WSJ’s The Future of Everything

I wish I had the time to listen to all of these and give you guys a review of each of them. You can see I’m biased towards science and history, with very little regarding literature. But there are great podcasts for those topics as well, it’s just that I haven’t gotten around to even searching for them. Besides, I read a lot of books, so I have less of an interest in podcasts that discuss topics that I have more firsthand contact.

Audiobooks

I cannot recommend audiobooks enough. At first, I was really hesitant to listen to books, but I found that the experience is delightful. Audiobooks are more than just a person reading a book out loud. Rather, professional voice actors narrate the contents for you, and it feels like your own personal storyteller.

A good narrator will have distinct voices for different characters, will vary tone and narration speed depending on the mood and will absolutely make the story come to life for you. Non-fiction books are also available as audiobooks and narrators know how to strike the balance between the seriousness of the text and a compelling listening experience. So, pick whatever book you’d like to get acquainted to and listen to your heart’s content.

There are various audiobook providers, but Amazon’s Audible has been my favourite for years now. Recently they even changed the way their subscriptions work, providing tons of free titles as part of your membership. This means lots of classics that show up on the IMAT, so it is a great deal!